Nearly 15 years ago – in 2008 – Uptime Institute presented a paper titled, The Gathering Storm. The paper was about the inevitability of a big struggle against climate change, and how that might play out for the power-hungry data centre and IT sector. The title echoed Winston Churchill’s book describing the lead up to World War II.

The presentation was prescient, discussing the key role of certain technologies such as virtualisation and advanced cooling, an increase in data centre power use, the possibility of power shortages in some cities, and growing legislative and stakeholder pressure to reduce emissions. But seen from today, in 2022, one fact stands out: the storm is still gathering, and, for the most part, most of the industry is as yet unprepared for its intensity and duration.

This may be true both literally – a lot of digital infrastructure is at risk, not just from storms, but gradual climate changes – and metaphorically. In the next decade, demands for operators to be ever more sustainable will rain down from legislators, planning authorities, investors, partners, suppliers, customers and the public. And increasingly, many of these will expect to see verified data to support claims of greenness, and for organisations to be held to account for any false or misleading statements.

Incoming legislation

If this sounds unlikely, then look at two different reporting or legal initiatives, both in fairly advanced stages. The first is the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, known as TCFD, a climate reporting initiative created by the international Financial Stability Board. TCFD reporting requirements will soon become part of financial reporting for public companies in the US, UK, Europe, and at least four other jurisdictions in Asia and South America.

Reports must include all financial risks associated with mitigating and adapting to climate change. In the digital infrastructure area, this will include remediating infrastructure risks (including, for example, protecting against floods, reduced availability of water for cooling, or the need to invest to deal with higher temperatures), risks to the equipment or service providers, and, critically, any potential exposure to financial or legal risks resulting from a failure to meet stated and often ambitious carbon goals.

A second initiative is the European Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) recast, set to be passed into European Union law in 2022 and to be enacted by member states by 2024 (for the 2023 reporting year). As currently drafted, this will mandate that all organisations with more than approximately 100kW of IT load in a data centre must report their data centre energy use, data traffic storage, efficiency improvements and other data, and perform and publicly report periodic energy audits. Failure to show improvement may result in fines.

While many US states, and of course many other countries, may lag far behind in such reporting, the storm is global, and TCFD- and EED-type legislation is likely to be spread around the world.

Taking sustainability seriously

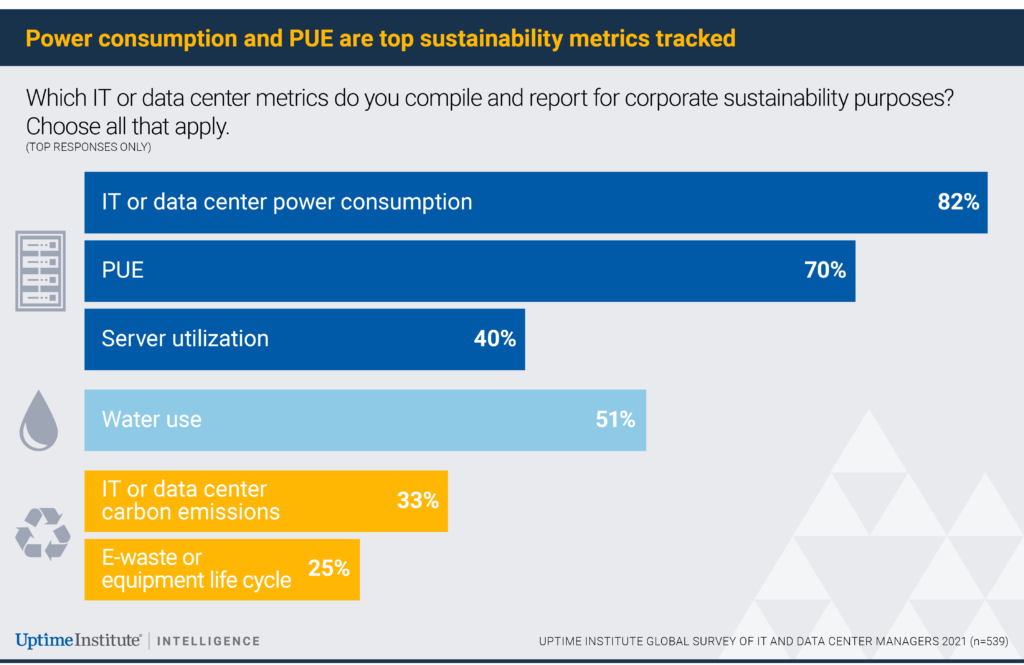

As the data from an Uptime Institute survey shows in the chart below, most owners and operators of data centres and digital infrastructure have some way to go before they are ready to track and report such data – let alone demonstrate the kind of measured improvements that will be needed. The standout number is that only about a third even calculate carbon emissions for reporting purposes.

For all these reasons, all organisations have, or should have, a sustainability strategy to achieve continuous, measurable and meaningful improvement in operational efficiency and environmental performance of their digital infrastructure (this includes enterprise data centres, and IT that is in colocation and public cloud data centres). Companies without a sustainability strategy should take immediate action to develop a plan if they are to meet the expectations or requirements of their authorities, as well as their own investors, executives and customers.

Developing an effective sustainability strategy is not a simple reporting or box-ticking exercise, nor a market-led flag-waving initiative. It is a detailed, comprehensive playbook that requires executive management commitment and the operational funding, capital and personnel resources necessary to execute the plan.

Creating a sustainability strategy

For a digital sustainability strategy to be effective, there must be cross-disciplined collaboration, with the data centre facilities (owned, colocation and cloud) and IT operations teams working together, along with other departments, such as procurement, finance and sustainability.

Uptime Institute has identified seven areas that a comprehensive sustainability strategy must address: greenhouse gas emissions; energy use (conservation, efficiency and reduction); renewable energy use; IT equipment efficiency; water use (conservation and efficiency); facility siting and construction; and disposal or recycling of waste and end-of-life equipment.

Effective metrics and reporting relating to the above areas are critical. Metrics to track sustainability and key performance indicators must be identified and data collection and analysis systems put in place. Defined projects to improve operational metrics, with sufficient funding, should be planned and undertaken.

Many executives and managers have yet to appreciate the technical, organisational and administrative/political challenges that implementing good sustainability strategies will likely entail. Selecting and assessing the viability of technology-based projects is always difficult, and will involve forward-looking calculations of costs, energy and carbon risks. For example, buying renewable energy can be both financially risky and complicated, requiring specialist expertise; and extensive negotiations will be needed with supply chain partners and regulators, to agree on what and how to report. For all operators of digital infrastructure, the first big challenge is to acknowledge that sustainability has now joined resiliency and become a top-tier imperative.