For a while now, law enforcement have been using biometrics to help fight crime, and more recently, advances have been happening in the field of facial recognition technology.

The idea behind biometric technology such as this is to improve the ‘quality and efficiency’ of policing, whilst reducing costs. Sadly, whenever I hear ‘to reduce costs’ these days I think, ‘to cheap out’.

However, that doesn’t seem to have been the case here, as back in 2019, the home office did plan to invest £97 million into a wider biometric strategy to help keep us safe. But when this technology is only helping some of us, is that still beneficial, or just a disaster waiting to happen?

Well, The Council of Europe seem to be of the latter opinion, who have called for certain applications for facial recognition to be banned altogether, alongside strict rules to avoid significant privacy and data protection risks posed by the increased usage of this technology.

And this isn’t the usual, steal your credit card details type privacy breach, we’re talking human rights violations.

In a new set of guidelines addressed to governments, legislators and businesses, the Council of Europe has proposed that the use of facial recognition for the sole purpose of determining a person’s skin colour, religious or other belief, sex, racial or ethnic origin, age, health or social status should be prohibited.

Ironically, facial recognition technology as it stands is actually more likely to pick up on darker skinned faces. A growing body of research has exposed divergent error rates across demographic groups, with the poorest accuracy consistently found in subjects who are female, black and 18-30 years old.

In fact, in the landmark 2018 ‘Gender Shades’ project, an intersectional approach was applied to appraise three gender classification algorithms, including those developed by big dogs such as IBM and Microsoft.

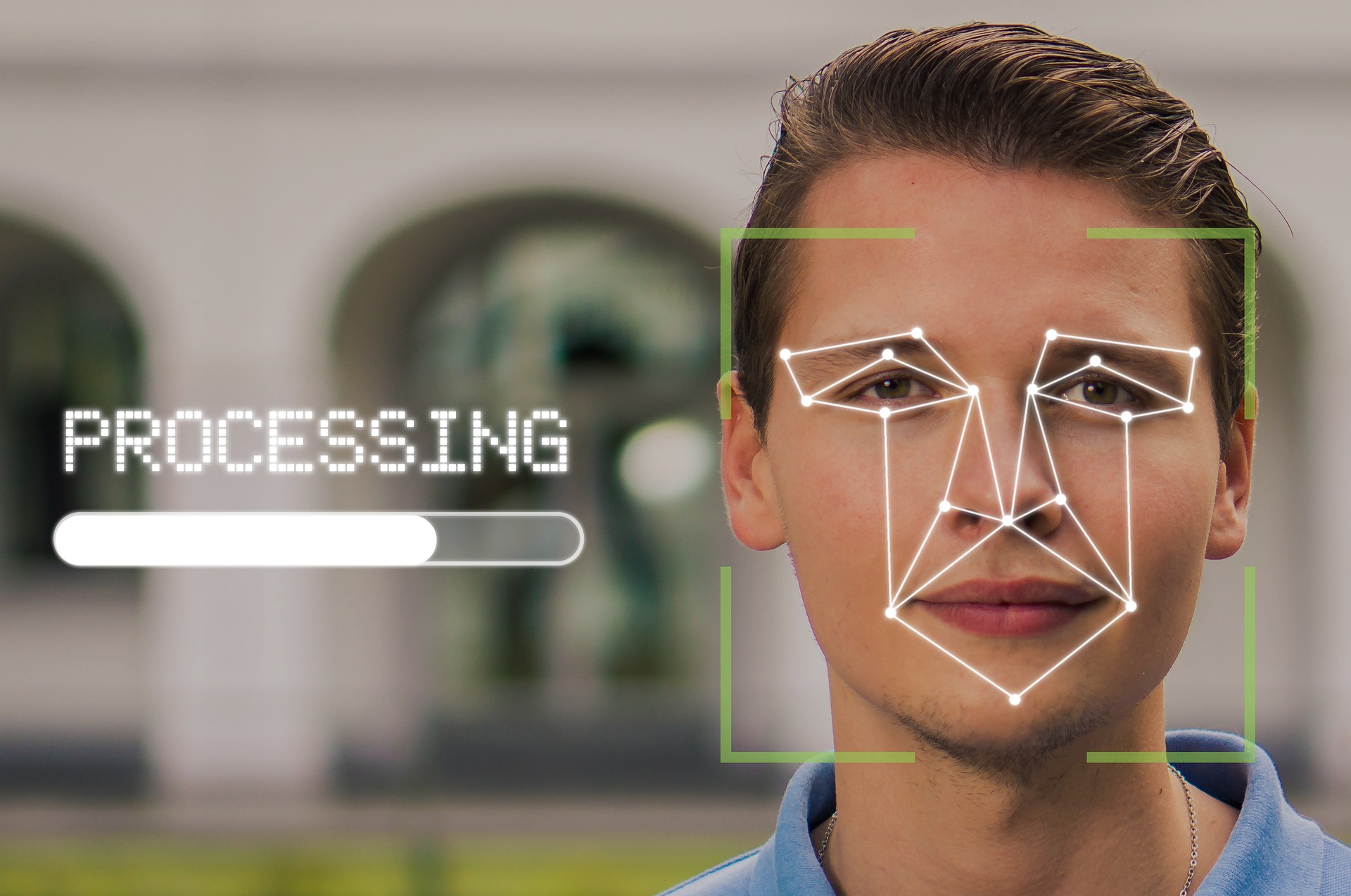

Subjects were grouped into four categories: darker-skinned females, darker-skinned males, lighter-skinned females, and lighter-skinned males. All three algorithms performed the worst on darker-skinned females, with error rates up to 34% higher than for lighter-skinned males. And when the only stock image for ‘facial recognition’ available to you to illustrate your article is one depicting a white male face, it really is a matter of case and point.

The European Council also stated that the bans suggested should also be applied to ‘affect recognition’ technologies. This is the type of (terrifying) technology that can literally detect what you are thinking or feeling, identify emotions, personality traits and mental health conditions. A little too personal when these traits could pose significant risks in fields such as employment or access to insurance and education.

And even without these risks to employment or education, for me, this is a step too far as it is. I don’t even want to be in my own brain half the time, let alone have anyone else root about in there. I’d probably cause the machine to malfunction and start screaming (if it had such a function.)

Jokes aside, this does beg the question, how can recognition technology tell someone your inner most feelings, yet still can’t accurately tell the difference between a white face and a black face? And if this is still the case, why the hell has this technology, that by the sounds isn’t fit for purpose, been rolled out in the first place?

This editorial originally appeared in the Data Centre Review Newsletter February 26, 2021. To ensure you receive these editorials direct to your inbox, you can subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.